MiniDisc: Sony’s Digital Audio Format, History, and Legacy

What MiniDisc was, how it worked, and how it was used

MiniDisc was Sony’s recordable digital audio format, introduced in 1992. It paired a rewritable magneto-optical disc with ATRAC compression to make portable digital recording feasible on consumer hardware. Unlike cassettes or compact discs, MiniDisc allowed users to record, edit, rename, and rearrange tracks directly on the device without degrading the original audio.

Sony created MiniDisc to address a gap between cassette and compact disc as everyday recording media. Cassettes were portable but wore out and drifted mechanically. Compact discs offered higher fidelity, but recording remained expensive and poorly suited to mobile use. MiniDisc occupied the space between them, combining digital sound with the ability to reuse recordings, revise them, and change track order freely.

Viewed today, MiniDisc does not fit cleanly into later format categories. It looks like an optical disc, behaves like digital storage, and encourages forms of interaction later file-based players would discard. The format was not optimized around fidelity alone. It was shaped around control, editability, and personal ownership at a moment when most digital audio remained fixed and read-only.

Part of the ObsoleteSony MiniDisc Archive, covering MDLP, NetMD, Hi-MD, and the broader context surrounding the format.

What Is MiniDisc?

MiniDisc is a recordable digital audio format built around a rewritable magneto-optical disc and Sony’s ATRAC compression system. Each disc is sealed inside a protective cartridge that shields the recording surface from dust and handling while maintaining stability during movement.

Recording defined the format’s purpose. Playback mattered, but MiniDisc differentiated itself by what happened after audio was captured. Tracks could be renamed, reordered, split, or deleted directly on the device without rewriting the recording or altering sound quality.

In daily use, MiniDisc functioned less like an optical disc and more like a compact digital workspace. Discs were reused without hesitation, overwritten repeatedly, and reorganized as listening habits changed. The physical interaction reinforced that behavior. The shutter sliding open, the disc being drawn into the mechanism, and the brief mechanical whir signaled a system built around deliberate handling rather than passive consumption.

How MiniDisc Works

MiniDisc records audio using magneto-optical technology. The 64 mm disc is housed inside a 72 × 68 mm cartridge, keeping the recording surface sealed during handling. During recording, a laser heats a microscopic point on the disc from one side while a magnetic head on the opposite side alters its magnetic orientation. Once cooled, the data remains fixed. Playback uses a lower-power laser that reads the information without modifying it.

ATRAC compression made this approach workable on portable hardware. By reducing data size while remaining efficient to decode, ATRAC enabled real-time recording and playback on battery-powered devices years before general-purpose processors could manage uncompressed audio comfortably.

Each disc maintains a Table of Contents that functions as a map rather than a timeline. Editing updates this index instead of rewriting audio, allowing tracks to be moved or renamed almost instantly. An internal memory buffer, typically ranging from roughly 10 to 40 seconds depending on generation, reads audio ahead of playback, making MiniDisc players unusually resistant to skipping during movement.

Why Sony Created MiniDisc

MiniDisc did not begin as a clean attempt to reinvent personal audio. It emerged under strategic pressure. By the late 1980s, Philips had already learned that winning a format war did not guarantee lasting control. The Compact Cassette spread worldwide, but its open licensing limited Philips’ leverage once the market stabilized. When digital recording returned to the consumer conversation, ownership mattered as much as innovation.

That experience shaped Digital Compact Cassette. Announced in 1990, DCC preserved the cassette form factor, maintained backward compatibility, and relied on fixed compression to make digital recording feasible without disrupting existing habits. The design favored continuity and predictability. Sony interpreted the announcement as a warning. Allowing the next recording format to be defined elsewhere would place Sony in a reactive position.

MiniDisc shifted internally from experiment to platform in response. Sony pushed the format into public release before its technical boundaries were fully resolved. Compression evolved, hardware changed after launch, and criticism did not slow revision. MiniDisc existed because Sony moved early under pressure, and that pressure gave the format enough flexibility to outlast DCC by more than a decade.

When MiniDisc Was Released

Sony publicly unveiled the MiniDisc format in September 1992 alongside the first wave of supporting hardware and blank media. The announcement marked Sony’s formal commitment to MiniDisc as a consumer recording platform rather than an internal experiment.

The first commercial products arrived in Japan later that year, led by the MZ-1 portable recorder alongside playback-only units. From the beginning, MiniDisc was presented as a recording system rather than a playback accessory. Demonstrations focused on hands-on editing and device interaction, signaling Sony’s intent to establish MiniDisc as a durable standard rather than a transitional product.

How the MiniDisc Format Evolved

MiniDisc did not remain static after launch. Unlike most physical media formats, it continued to change as real-world use exposed its limitations. Early criticism did not halt development, and Sony did not treat the first generation as definitive. Hardware shifted, workflows adjusted, and expectations followed.

MDLP, introduced in 2000, marked the first major change. By adopting ATRAC3 compression, it extended recording time and repositioned MiniDisc as a practical everyday recorder rather than a direct CD alternative. LP2 roughly doubled capacity at around 132 kbps, while LP4 extended recording time further at the expense of fidelity.

NetMD followed in 2001 and introduced USB connectivity. In theory, it connected MiniDisc to personal computers. In practice, transfers were mediated through SonicStage software and constrained by restrictive digital rights management. Legal caution shaped the system more than usability, turning a simple connection into a persistent source of friction.

Hi-MD arrived in 2004 as the format’s most ambitious revision. It introduced 1 GB discs, supported uncompressed PCM recording, and added a true data storage mode alongside audio. By the time MiniDisc reached this level of technical maturity, the surrounding definition of personal audio had already shifted. Each revision addressed real constraints, but the market was changing faster than the format could adapt.

Why MiniDisc Failed

MiniDisc struggled because its strengths no longer aligned with how people were beginning to manage music.

High early prices limited adoption. Players carried premiums, blank media remained costly, and Sony’s ecosystem strategy compounded friction rather than reducing it. Pre-recorded MiniDisc albums were scarce, leaving the format dependent on user-driven recording just as simpler digital alternatives appeared.

Sound quality perception also shaped outcomes. Early ATRAC revisions introduced audible compromises that defined first impressions among attentive listeners. Later improvements arrived after those impressions had hardened.

Timing closed the window. Affordable CD burners spread rapidly, blank CDs became inexpensive, and portable CD players grew more reliable. In 2001, the iPod reframed expectations by offering a centralized, pocket-sized library instead of a disc-based collection. MiniDisc remained organized around individual media units. File-based players removed that final layer of friction, and the habits MiniDisc relied on faded soon after.

Is MiniDisc Still in Production?

MiniDisc recorders are no longer produced. Sony gradually ended hardware development during the 2010s as consumer audio moved toward file-based playback and solid-state storage.

Recordable MiniDisc media remained in production longer to support existing users and professional workflows. In February 2025, Sony ended production of all remaining recordable MiniDisc blanks, closing the format’s manufacturing lifecycle. Continued use now depends entirely on remaining stock and reused media.

Today, MiniDisc persists as a niche. Collectors restore hardware and continue to use the format for tasks that remain unusually direct and tactile. Its role as a consumer standard has fully passed.

MiniDisc’s Legacy

MiniDisc treated recorded audio as something that could be changed after it was captured, rather than fixed in place. It normalized behaviors that later became commonplace: non-linear editing, metadata, portable organization, and immediate access to recordings, all executed on dedicated hardware rather than general-purpose computers.

The format introduced everyday digital practices before smartphones and streaming systems made them invisible. It allowed users to rename, reorder, and restructure audio non-destructively on a portable device, treating music as information rather than as a finished artifact.

MiniDisc occupies a transitional position in media history. It belongs to a period when ownership and physical interaction still shaped listening, while introducing workflows that later reappeared in file-based and streaming systems.

MiniDisc Timeline

2000: MDLP extends recording time

2006: Fully mature late-generation portable recorders arrive

MiniDisc FAQ

Is MiniDisc basically a small CD, or something different?

It is different. MiniDisc uses a laser, but it does not behave like a linear optical disc. Audio is stored as data blocks referenced by an internal index. Track order, names, and structure can be changed without rewriting the recording itself. In practice, MiniDisc behaves more like rewritable digital storage than a CD.

Why could MiniDisc edit tracks instantly when CDs could not?

Because MiniDisc treats structure and audio separately. Editing changes the Table of Contents, not the sound data. Compact discs write audio in a fixed sequence. Any structural change requires rewriting the disc, which prevents instant edits.

Does MiniDisc sound worse than CDs?

Early ATRAC versions made compromises that were audible to some listeners and shaped the format’s reputation. Later revisions improved noticeably, but those changes arrived after CD playback and file-based audio had already defined expectations. For most users, sound quality was stable and acceptable, with editing and recording taking priority.

Was Sony the only company making MiniDisc recorders?

No. Sony created and controlled the format, but MiniDisc hardware was produced by several manufacturers. Sharp, Panasonic, Pioneer, Kenwood, and Aiwa all released players and recorders at different points. MiniDisc operated as a multi-brand ecosystem, not a single-vendor platform.

Why do some people still use MiniDisc today?

Because it offers a workflow that later formats removed. Recording, editing, and organization happen directly on the device, with physical media and immediate feedback. For certain uses, that directness remains useful.

Can you still transfer MiniDiscs to a computer today?

Yes, but not through modern file transfer methods. Most archives are made in real time using optical or analog output into a computer or recorder. It is slower, but reliable, and preserves the original recording without format conversion.

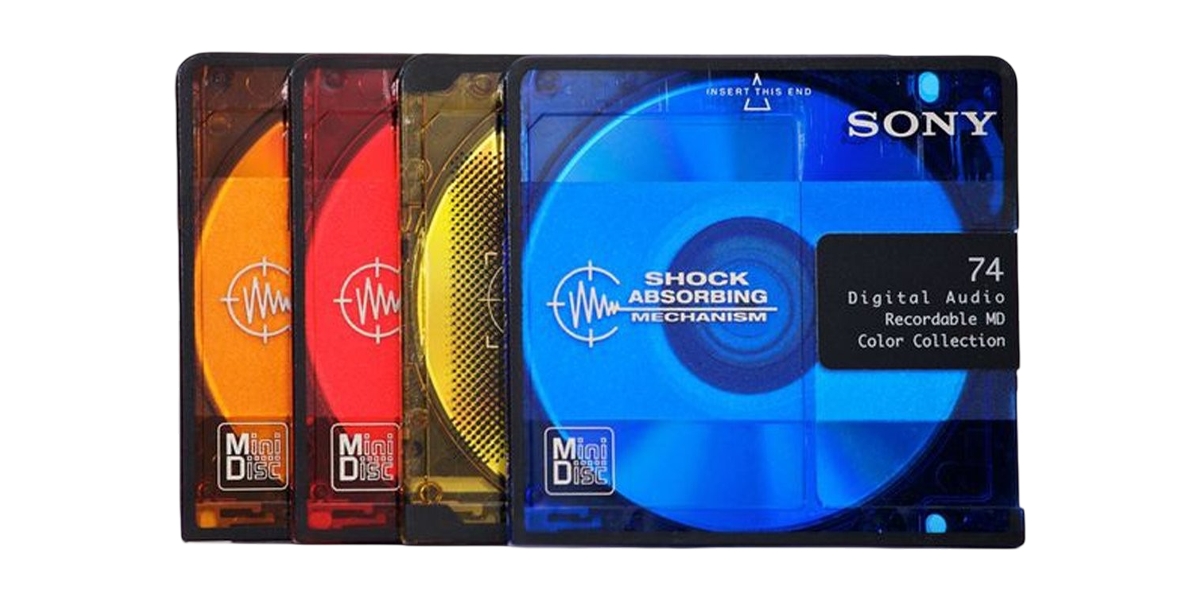

MiniDisc remains such an incredible community supported format. The discs themselves are essentially bullet proof running fine with or without the plastic slipcase that everyone seemed to lose. But best of all are all the specialty blank media releases from countless companies. Who doesn't love a good Neige or specialty-colored club blank?

I miss this format within the depths of my soul. They truly felt like a natural progression from cassette tapes and protected the media from scratches. It would be pretty neat if they brought this back in higher density, and somehow, of archival quality.