Inside the Rushed Development of MiniDisc

The Race to Redefine Digital Audio

In the early 1990s, Sony stood at the pinnacle of innovation.

Born from the ashes of World War II, the company had spent nearly half a century shaping how the world listened to music. From the early transistor radios, to the Walkman and the Discman, Sony defined portable audio.

As the world shifted toward digital audio, Sony saw an opportunity to redefine the next era of music.

But ambition came at a cost. In chasing innovation, Sony pursued a vision that often outpaced what its own technology could deliver.

This is the story of how a rushed launch shaped the legacy of one of Sony’s most ambitious audio formats.

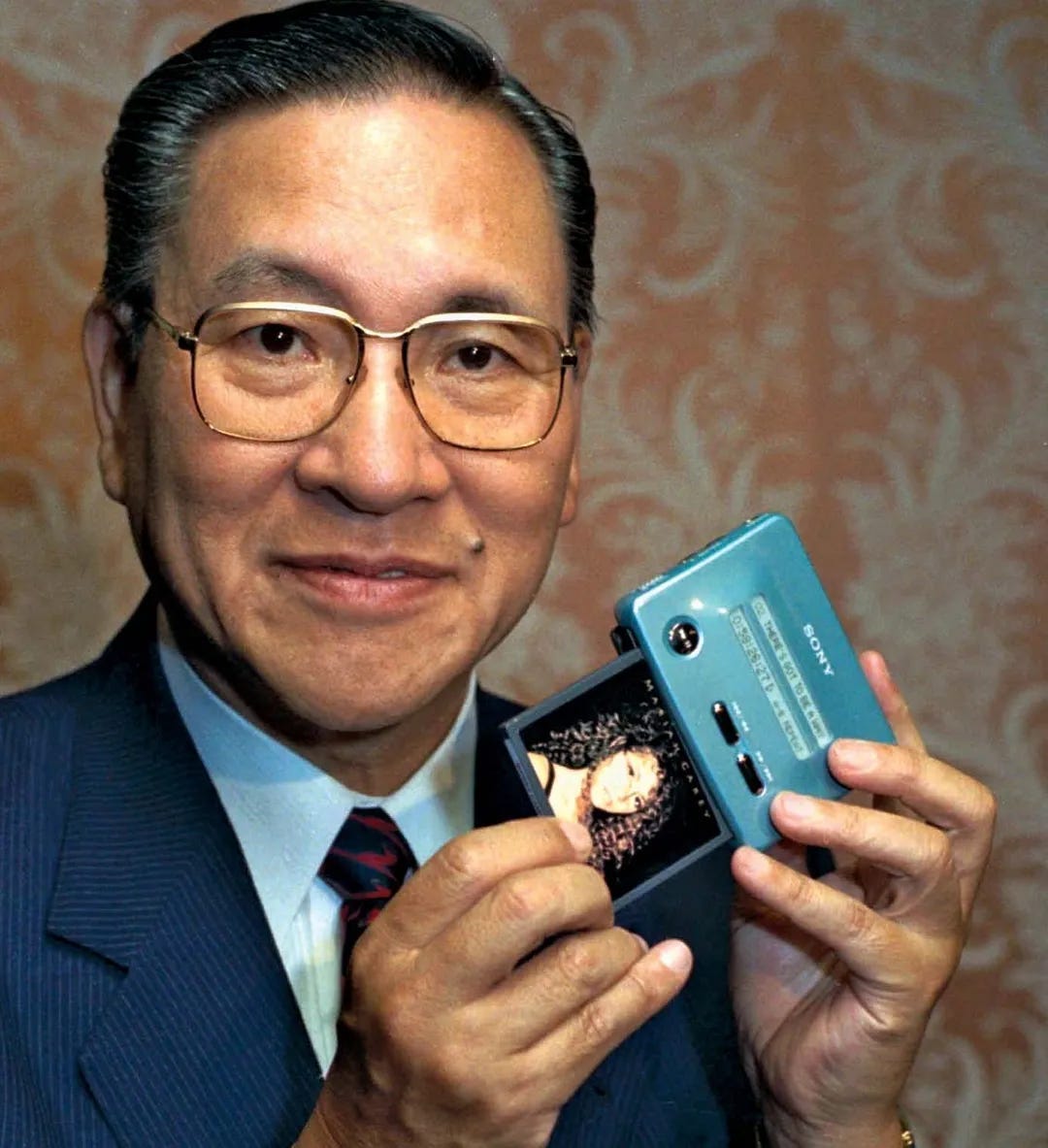

One of the driving forces behind the project was Norio Ohga. A classically trained opera singer with a sharp ear and sharper instincts, Ohga first came to Sony in the 1950s after sending the company a detailed critique of a tape recorder’s sound quality. Rather than take offense, Sony’s founders were impressed and invited him in.

He quickly became indispensable. Ohga pushed Sony toward higher fidelity audio, helped lead the development of the Compact Disc, and later steered the company into the world of entertainment. By 1982, he had become president. By 1989, he was CEO. At a time when Sony was trying to shape the future of digital media, Ohga was the one defining the path forward.

By 1991, Sony’s next challenge had taken form.

Philips, the Dutch electronics company that had partnered with Sony to develop the CD, was now promoting a new format of its own: the Digital Compact Cassette. Ohga recognized it immediately as a strategic threat. If Philips succeeded in making DCC the next digital standard, Sony risked losing control of the very category it helped invent. Worse, it might be forced to pay royalties to a rival for every unit sold.

Ohga wasn’t willing to let that happen.

Sony moved quickly. The decision to create a rival format was made at the top, and engineers were given their marching orders. The new format would be recordable, using magneto-optical (M.O.) disc technology, and it would be compact enough for portable use.

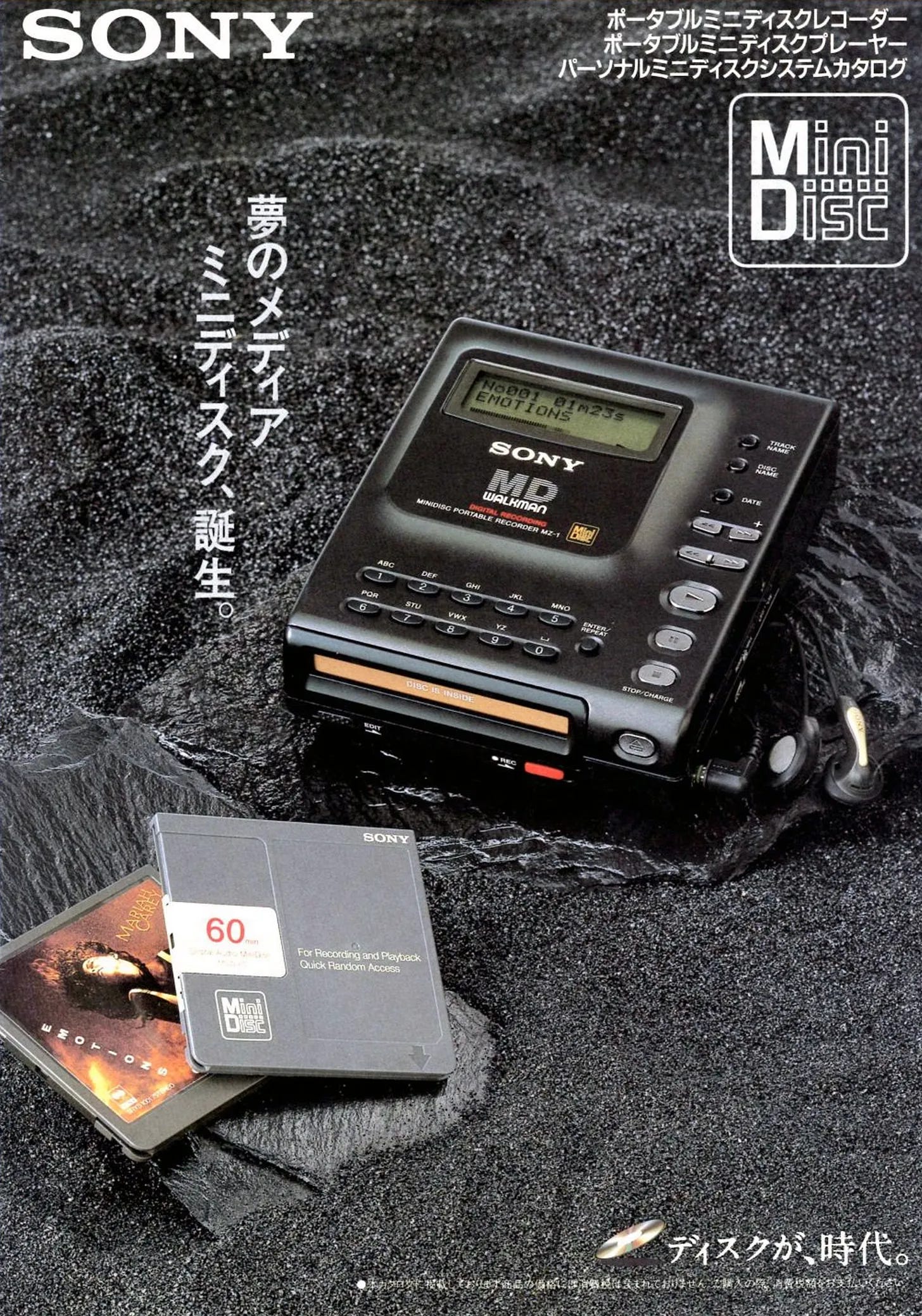

The result was the MiniDisc.

The concept was bold. Maybe too bold. While engineers were still scrambling to make the core technology viable, Ohga unveiled the first MiniDisc mockup to the public in 1991. It was futuristic, and impossibly small. Sony had hoped to match the dimensions of its latest cassette Walkman, but that goal quickly ran into technical limitations.

The hardware wasn’t ready. Fitting all the components needed to handle disc loading, optical reading and writing, memory buffering, and digital encoding into such a compact form was impossible. The mockup was a promise the engineers couldn’t yet fulfill. The public had seen the vision, and now they expected it.

Internally, pressure kept building. Engineers worked around the clock to maintain portability while integrating all the mechanisms the system required, focusing on fitting an entire digital studio into a compact design small enough to carry.

MiniDisc was designed not just to play music, but to record, edit, rearrange, and delete. Sony developed its own compression format, ATRAC, to make this possible. A single disc could hold 74 minutes of music with error correction, skip protection, and a Table of Contents system for non-linear editing. Users could name tracks, split and group them, or re-sequence playlists in real time.

The concept was far ahead of what most people were used to. And Sony was betting everything on it.

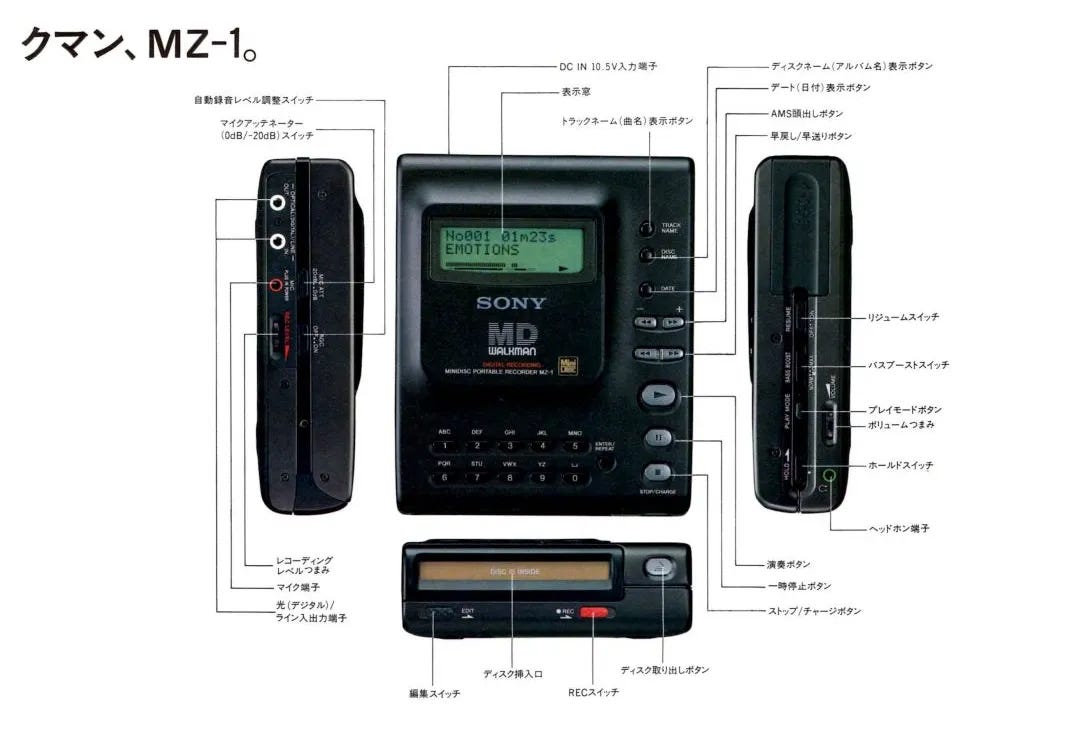

The first MiniDisc recorder was designed as a flagship product that would introduce the world to an entirely new format.

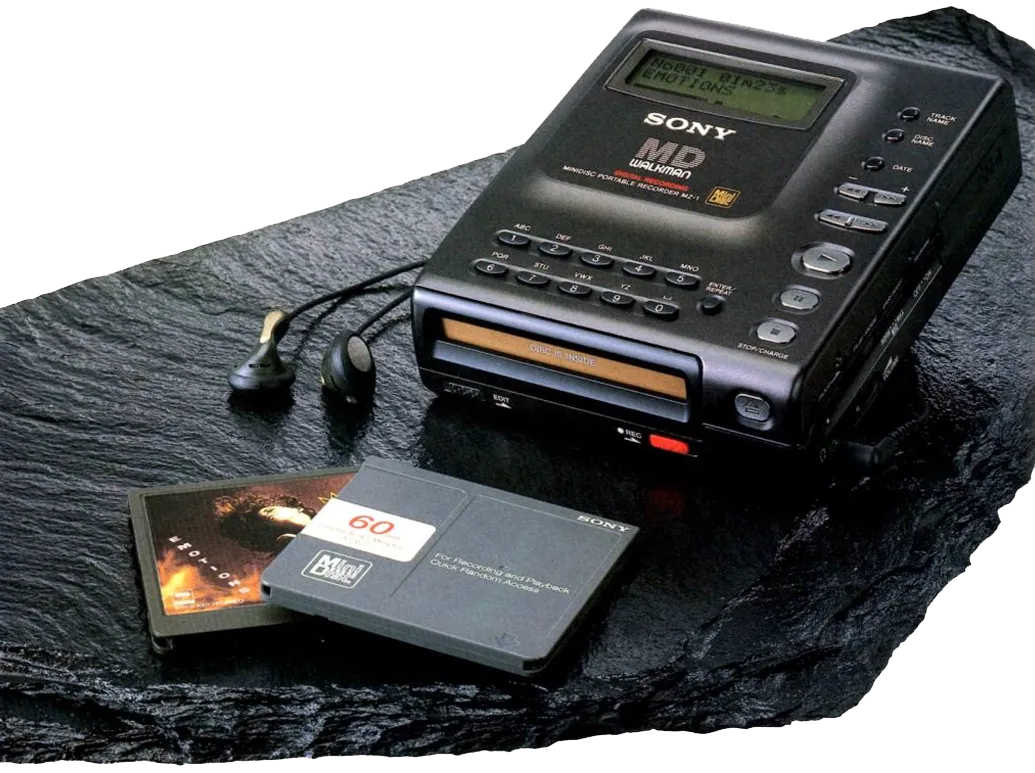

Sony named it the MZ-1, marking the start of a new product line. This model was created to demonstrate the full range of MiniDisc’s capabilities. It could record and edit audio, accept digital inputs, and offer portable playback. But building it meant overcoming a series of technical challenges that pushed Sony’s engineering team to the edge.

The MZ-1 demanded a level of manufacturing precision that Sony had never attempted at this scale. The magneto-optical drive depended on perfect alignment between the laser and magnetic head. Even microscopic errors could disrupt playback or recording. Fine-tuning the mechanism required intense focus and constant adjustments.

The workload on engineers quickly became overwhelming. Shizuo Takashino, head of Sony’s General Audio division, recognized the toll it was taking. He sent letters to the families of engineers and arranged hotel suites at the Shinagawa Prince so employees working late wouldn’t need to commute. Managers even brought them clean clothes and essentials when they couldn’t go home. Takashino would later become one of Sony’s top executives, but even then he was known for being present, supportive, and deeply involved in the work.

Production took place at the Bonson Sakado Factory, where nearly every component had to be designed from scratch. The slot-load mechanism, adapted from in-car cassette players, was a clever solution that fit the form factor but introduced its own complications. It required precise calibration to function smoothly and was sensitive to movement, which sometimes caused glitches during recording.

Sony also depended on external suppliers for critical parts like the spindle motor and optical pickup. These components had to be refined in-house to meet Sony’s exact standards. The final result was a device that was technically impressive but physically large, heavy, and demanding. The MZ-1 could barely complete playback of a single disc on one charge. In contrast, the average Walkman at the time could deliver ten or more hours of audio using just two AA batteries.

Sound quality posed another challenge.

The first version of ATRAC compression made it possible to store CD-length audio on the smaller disc using a five-to-one compression ratio. But the tradeoff was noticeable. High frequencies suffered, and subtle artifacts began to appear. Internal tests showed that the audio lacked the depth and clarity of a standard CD, and audiophiles quickly picked up on the difference.

Sony understood the codec needed improvement, and in time it delivered. Later versions of ATRAC significantly enhanced audio quality and helped win over many of the early skeptics. But by that point, the damage had already been done. First impressions had taken hold, and for many, the MZ-1 had failed to live up to its potential.

In November 1992, after months of long nights, delays, and engineering breakthroughs, the MZ-1 finally launched. Sony backed it with a full campaign that included commercials, hands-on demos, and high expectations. But once the product reached store shelves, reality quickly set in.

The MZ-1 sold for 79,800 yen, which was around 650 US dollars. That price put it far out of reach for the youth market Sony had hoped to capture. Students and tech enthusiasts admired the innovation but couldn’t justify the cost. Older buyers who could afford it often felt let down by the compressed audio quality. Sony had aimed for both audiences and ended up missing both.

Despite its flaws, the MZ-1 introduced many of the features that would later define MiniDisc. Over time, Sony addressed the issues that held this first model back. Later devices became smaller and lighter, battery life improved, and ATRAC compression saw major refinements. But by then, the early impression had already shaped public perception. The format had launched with promise, but not with polish.

Another challenge was the lack of support from other manufacturers. Unlike the Compact Disc, which had been developed jointly with Philips and gained broad industry backing, MiniDisc was launched by Sony alone. Few third-party companies adopted it in the early years, which limited device variety and kept prices high. The catalog of pre-recorded MiniDiscs remained small and expensive. Major labels were hesitant, and most consumers were still used to buying music that was ready to play. MiniDisc asked them to do the work themselves by creating their own recordings and mixes.

Sony believed there was time. Internally, the assumption was that home CD-burning would remain out of reach for most people. That belief gave MiniDisc a sense of strategic security. But CD-R drives became affordable much faster than expected. Within just a few years, custom CD mixes became easy and cheap to make at home. MiniDisc’s main selling point no longer felt essential.

The product also suffered from unclear messaging. MiniDisc was positioned as a music player, a recorder, and a digital editing tool all in one. But that flexibility made it hard to explain. Some viewed it as a professional recorder. Others saw it as a futuristic Walkman. In trying to be everything, it struggled to speak clearly to anyone.

In Japan, MiniDisc found early success. That domestic momentum gave Sony the confidence to expand it globally. But international markets were more cautious and price-sensitive. They held onto CDs longer, and new hardware adoption was slower. What worked at home didn’t translate abroad, and Sony was slow to adjust.

It wasn’t a bad product; in many ways, it was brilliant. However, Sony created a format, not a platform. Lacking the openness and collaboration of modern digital ecosystems, it missed where the market was headed. This failure wasn’t due to technology, but to poor timing, positioning, and strategy. Despite having the vision and engineering talent, Sony introduced the format too early, before the ecosystem could support it.

Things did improve. Later models became smaller, lighter, more affordable, and far more refined. ATRAC compression advanced significantly. Battery life improved. Costs dropped. In Japan, the format found real success and stayed relevant for years.

Sony’s rushed development didn’t stop MiniDisc from finding a niche, but it showed how much timing and market readiness can shape a product’s fate.

MiniDisc was fairly succesful in Europe. It remains my favourite Sony product, representative of Sony's marvellous engineering skills. I was 12 years old, and this product literally made me go into the tech industry. In 1992, this felt like the future.

I was always a big fan of MiniDisc and feel it never reached the potential it could have.