Why Was the PS3 $599 at Launch?

A Cost Breakdown of Sony’s PlayStation 3 Launch Price

When Sony launched the PlayStation 3 in late 2006, it arrived with two prices: $499 for a 20GB model and $599 for a 60GB model. Technically, there was a cheaper option. In reality, the $599 price became the console’s identity. It was the number people remembered, repeated, and argued about. Before long, it stood in for the system itself.

That wasn’t just because it was higher. The $599 model reflected the machine Sony had actually built. The $499 version removed features, but it did not change the core hardware that set the cost of the system. From Sony’s perspective, both models were the same console underneath.

To understand why the PS3 landed at $599, it helps to stop thinking about launch day reactions and look further back. The price was shaped by decisions Sony had already locked in years earlier. Those decisions weren’t accidents or last minute mistakes. They were early bets that favored technical ambition and long-term platform goals over the ability to adjust pricing later.

Some people also ask what $599 means today. Adjusted for U.S. inflation, $599 in 2006 works out to roughly $900 to $960 in 2025 to 2026 dollars, depending on how it’s calculated. That helps explain why the number still feels shocking. It does not explain why Sony chose it at the time.

Timing made the problem worse. Microsoft had already launched the Xbox 360 a full year earlier at $299 and $399. Nintendo released the Wii alongside the PS3 at $249.99. By the time Sony showed up with a $599 console, the Xbox 360 already had a growing game library, a functioning online service, and millions of players. For buyers, the comparison was simple. It was $599 for what the PS3 might become versus $399 for something that was already delivering. Part of that difference came down to strategy. The Xbox 360 shipped games on DVD-ROM, while Sony baked a next-generation disc format into every PlayStation 3.

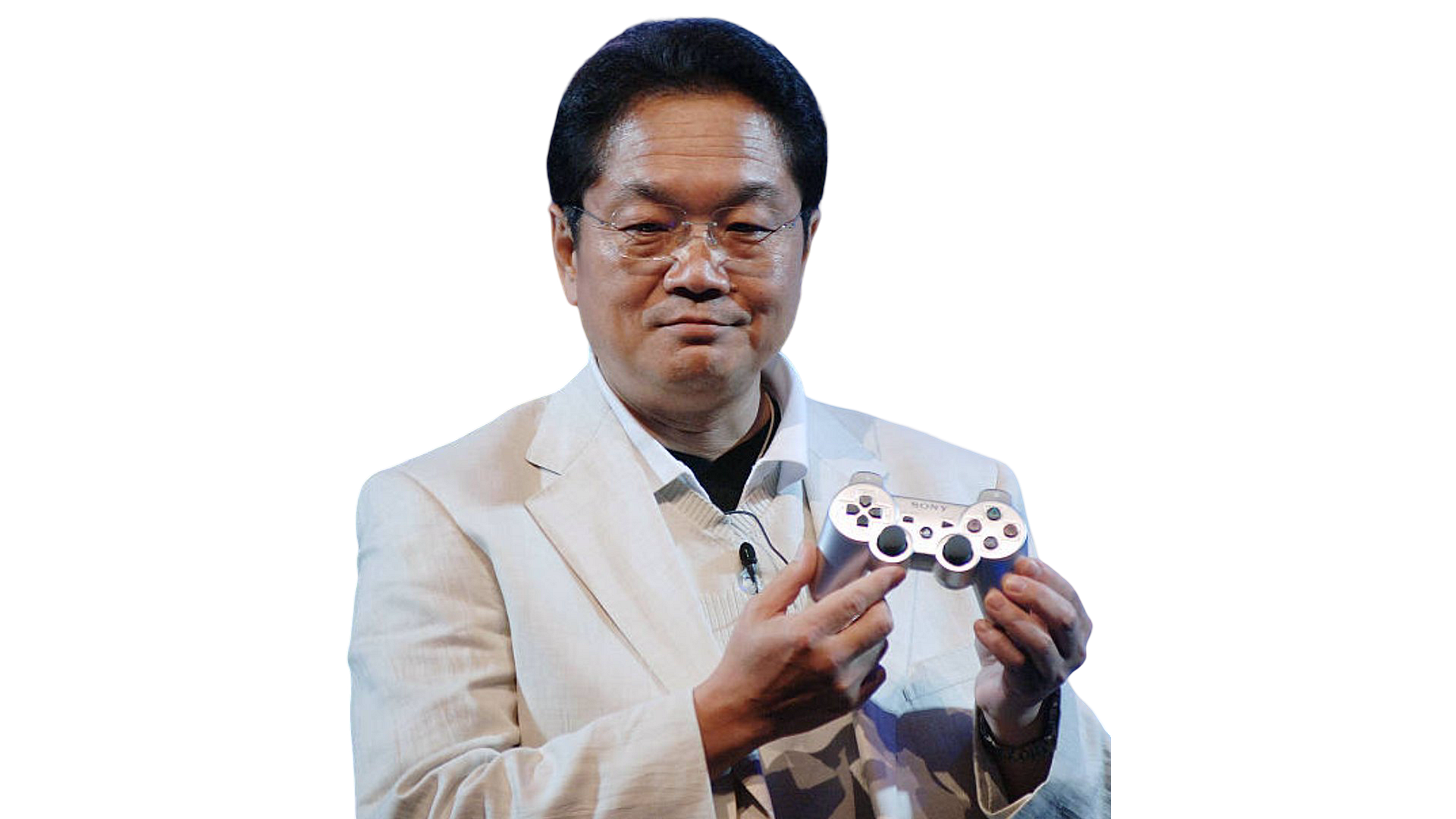

Sony’s attitude at the top reflected that gamble. Ken Kutaragi openly suggested that players would be willing to work more hours to afford the system, a sign of how much confidence Sony had in the PlayStation name. Internally, the PS3 was often framed as a long-term machine, sometimes described as a system meant to last ten years rather than a single console cycle.

The Price Was Set by Manufacturing Math

At launch, iSuppli estimated that the 20GB PlayStation 3 cost $805.85 to manufacture, while the 60GB model cost $840.35, excluding the controller, cables, and packaging. At a $499 retail price, Sony lost roughly $307 per unit on the 20GB model. The $599 model also sold at a loss despite the higher price.

The $100 price difference was optical, not structural. Both models bled money.

By mid-2008, cumulative hardware losses were estimated at approximately $3.3 billion. Those losses were not the result of a single misstep. They reflected a system whose early design choices pushed build costs beyond anything that could support a mass-market launch price.

Once the hardware was finalized, there was no version of the PlayStation 3 that could be built cheaply.

Blu-ray Set the Minimum Build Cost

One of the biggest reasons the PlayStation 3 was expensive was the Blu-ray drive. At launch, it added roughly $125 per unit to the cost of building the console.

Blu-ray relied on a 405-nanometer blue-violet laser that was still difficult to produce at scale in 2005 and 2006. Manufacturing yields were inconsistent, lifespans were limited, and supply was constrained. These problems affected cost, volume, and launch timing at the same time.

Blu-ray was not a feature Sony could simply remove to create a cheaper system. The PlayStation 3 was designed to function as a mass-market Blu-ray player during the high-definition format war, when standalone players still sold for far more than a game console. Removing the drive would have meant abandoning the strategy the system was built to serve.

In hindsight, the $3.3 billion in hardware losses can be read as the effective tax Sony paid to ensure Blu-ray defeated HD-DVD.

The RSX Locked Sony Into Early Silicon Costs

The PlayStation 3’s RSX graphics processor added about $129 per unit to manufacturing cost. Developed with NVIDIA, it entered production before cheaper fabrication processes were available.

The RSX was not unusually expensive for its performance. The problem was timing. It launched while chip manufacturing was still costly and before meaningful die shrinks could bring prices down. Waiting for a cheaper revision would have required delaying the console yet again.

Once the RSX entered production, removing or simplifying it would have meant redesigning the launch schedule rather than trimming costs.

The Cell Processor Shaped the Entire System

The Cell processor added an estimated $89 per unit in direct cost, but its influence reached far beyond the chip itself.

Cell shaped nearly every part of the PlayStation 3. The board layout, memory design, power delivery, and cooling system were all built around it. Its asymmetric architecture, combined with split memory of 256MB XDR for the CPU and 256MB GDDR3 for the GPU, forced developers to manage data carefully instead of relying on a unified pool.

That complexity did more than raise production costs. It made the system harder to work with early on. Many multi-platform games struggled to match their Xbox 360 versions in the first few years, not because the PS3 lacked power, but because Cell required tools and workflows studios were still learning. Asking players to pay $599 for a console where early third party games sometimes looked worse undermined the idea that this was a premium machine.

By the time Cell was finalized, changing it would have meant redesigning the console rather than simplifying it.

Backward Compatibility Multiplied the Burden

Early PlayStation 3 models included hardware based backward compatibility for PlayStation 2 games. Supporting that feature required additional silicon, a more complex motherboard, and higher power and cooling demands.

In practical terms, the console literally included the PlayStation 2’s Emotion Engine processor on the board. The PS3 was not emulating the previous generation. It was carrying the brain of another console inside itself.

Backward compatibility was not a small add-on. It increased board size, heat output, and manufacturing difficulty all at once. Each requirement made the system larger, hotter, and harder to produce efficiently.

Although Sony later removed backward compatibility from most models, it was part of the launch hardware and helped define the cost structure from day one.

Why the $499 Model Failed to Offer an Escape

The $499 PlayStation 3 did not give Sony a meaningful low-cost alternative.

While the 20GB model reduced storage and removed features, it kept the same core hardware that drove manufacturing cost. Both launch models used the same Blu-ray drive, RSX GPU, Cell processor, and system design.

More importantly, the $499 model did not include built-in Wi-Fi at a moment when wireless networking was becoming standard. A next-generation console that required an Ethernet cable to get online felt dated rather than forward looking. It also removed the flash memory card readers and premium trim found on the more expensive model.

The $599 version created a different frustration. Despite being sold as a high definition, Blu-ray focused machine, Sony did not include an HDMI cable in the box. Buyers had to purchase an expensive accessory just to use the system’s defining feature.

As a result, the cheaper model felt stripped down, while the expensive one felt unfinished. Neither changed the cost of making the console, and neither softened the price shock.

There was no simpler PlayStation 3 waiting to be produced cheaply.

Every Alternative Made Something Else Worse

By the time pricing was finalized, Sony’s options were already narrow. Delaying the launch again would have weakened its position in the high definition format war. Removing Blu-ray would have undercut the system’s purpose. Simplifying the hardware would have meant abandoning a design already locked into production.

Lowering the retail price would not have solved any of this. It would have only increased losses on hardware already being sold far below cost.

Every possible fix solved one problem by creating a larger one somewhere else. The $599 price was not ideal. It was simply the number left once the other paths were closed.

When the Price Finally Fell, the System Had Changed

The PlayStation 3 only became cheaper after the hardware itself changed. The PS3 Slim, released in 2009, used smaller manufacturing processes, simpler boards, and improved yields. These changes reduced production costs by as much as 70 percent in some estimates.

Only then did the PlayStation 3 become affordable to build. The launch models reflected a system designed before those efficiencies were possible.

The $599 PlayStation 3 price ultimately worked in one arena and failed in another. Blu-ray won the format war. Sony did not regain the generational dominance it enjoyed with the PlayStation 2.

The lesson carried forward. When the PlayStation 4 launched at $399, Sony still aimed high, but it finally accepted what the mass market was willing to pay.