PlayStation 3 Backward Compatibility Explained

How PS1 and PS2 games run on the PS3, why compatibility differs by model, and which systems still work

All PlayStation 3 models can play original PlayStation (PS1) games from disc natively using Sony’s built-in software emulator. From a practical standpoint, any PS3 remains a reliable and accurate way to play PS1 titles today.

PlayStation 2 backward compatibility exists only on a small group of early PlayStation 3 models. Full hardware compatibility is limited to launch-era “Fat” systems such as the North American and Japanese CECHAxx 60GB and CECHBxx 20GB models, which include original PlayStation 2 hardware on the motherboard. A second group of early systems, including CECHCxx and CECHExx revisions, use a hybrid approach that combines partial PS2 hardware with software emulation. All later models, including CECHGxx and every Slim and Super Slim, cannot play PS2 discs at all.

On systems with full hardware support, roughly 98 to 99 percent of the PlayStation 2 catalog runs correctly. Hybrid models fall into the low to mid-90 percent range, with failures concentrated around timing-sensitive engines, FMV playback, and streaming audio rather than random titles. This variation is architectural, not anecdotal, and explains both the confusion surrounding PS3 backward compatibility and why Sony removed the feature so quickly.

This guide explains how PlayStation 3 backward compatibility actually works, where it breaks, and what still matters in 2026. It covers graphics output changes, audio and FMV behavior, regional limitations, peripheral support, long-term reliability, and the real tradeoffs between full hardware, hybrid systems, and modern alternatives. If you are trying to decide which PS3 model to buy for PS1 or PS2 games today, this article breaks down every compatible revision and ends with clear buying advice grounded in ownership reality.

What Backward Compatibility Means on PlayStation 3

Backward compatibility on the PlayStation 3 was never meant to be permanent. It was a launch-era bridge, introduced to soften the transition away from the PlayStation 2 at a time when the PS3 was expensive, difficult to manufacture, and losing money at scale. In 2006, Sony was not designing for preservation or perfect fidelity. It was trying to make the jump to a new generation survivable.

The PlayStation 2 library already numbered in the thousands, and Sony aimed for broad coverage rather than edge cases. Even the most compatible PS3 models were never designed to guarantee flawless behavior across every game, peripheral, or regional variant. That tradeoff shaped every backward compatibility decision that followed and explains why the feature was costly, short-lived, and easy to remove once the PS3 began to stabilize.

There is one important exception. While PS2 backward compatibility on PS3 was brief and hardware-dependent, PlayStation 1 backward compatibility was not. Every PS3 includes a mature software emulator for PS1 titles that runs PS1 discs with near-perfect reliability. From a practical standpoint, any PS3 remains a dependable PS1 console, even though only a small subset can run PS2 discs.

The Hardware Decision That Made PS2 Backward Compatibility on PS3 Possible

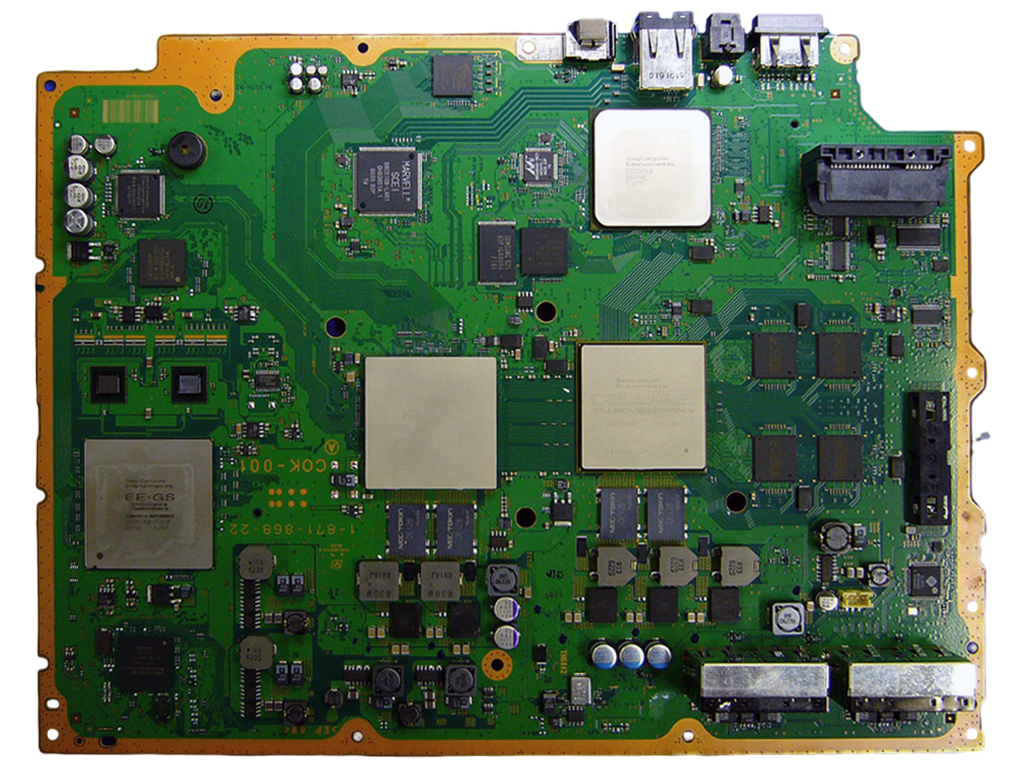

Sony’s first solution to PS2 backward compatibility on the PlayStation 3 was blunt and hardware-driven, following the same philosophy it had used a generation earlier. Just as the PlayStation 2 physically included key PlayStation 1 components, early backward-compatible PS3 models embedded PlayStation 2 hardware directly on the motherboard. In the most complete implementations, both the PS2’s Emotion Engine CPU and Graphics Synthesizer GPU were present, allowing PS2 code to run on dedicated hardware rather than being translated in software.

When a PS2 disc is inserted into these systems, the game executes on the same core processors it was written for. There is no full instruction-level emulation layer in between. The PS3 operating system handles coordination and I/O, but game logic remains largely native. This continuity is why full backward-compatible PS3 models achieve the highest overall PS2 disc compatibility of any non-PS2 hardware Sony shipped.

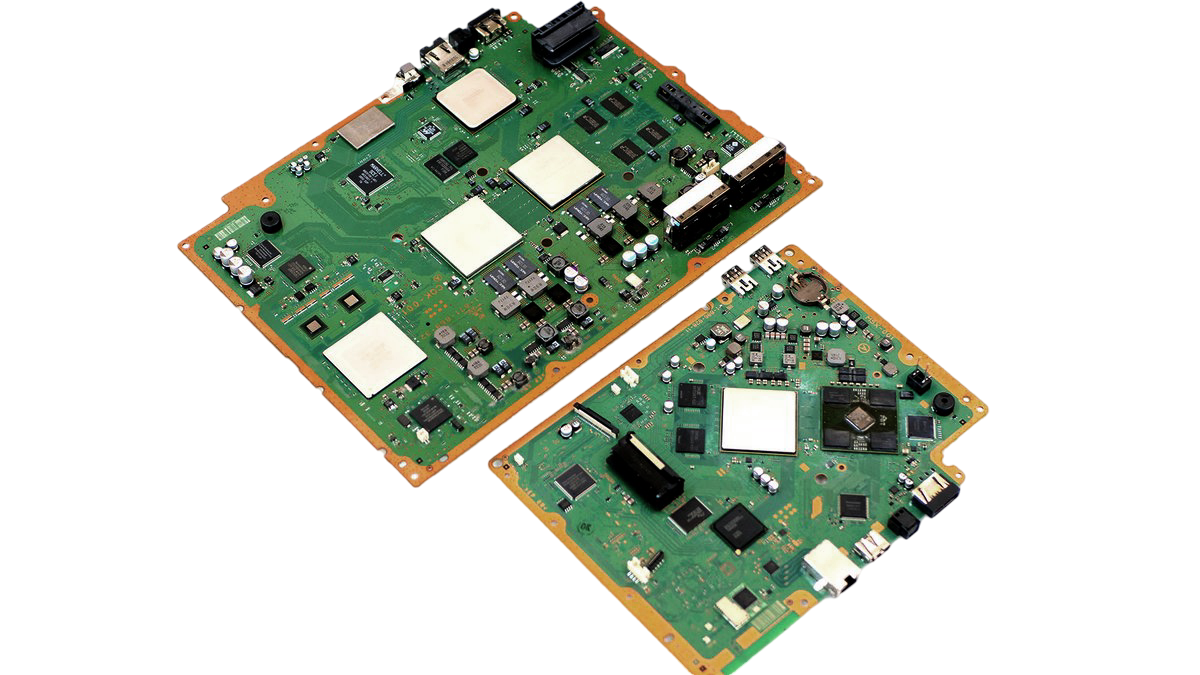

Sony later moved to a hybrid design. In these systems, the Graphics Synthesizer remains in hardware, but the Emotion Engine is removed and replaced with software emulation running on the PS3’s Cell processor. The change reduced manufacturing cost and heat output, but it also altered timing behavior in ways certain PS2 games are sensitive to, particularly those built around tight synchronization or continuous streaming.

As a result, full hardware backward compatibility is limited to specific launch-era systems, primarily North American and Japanese CECHAxx and CECHBxx models, including Japanese 20GB variants. European and Australian backward-compatible systems labeled CECHCxx, along with later North American CECHExx revisions, rely on the hybrid approach. Externally similar fat PS3 models such as CECHGxx do not support PS2 discs at all.

Why PS2 Backward Compatibility on PS3 Was Never Exact

Even on full hardware backward-compatible PS3 systems, PS2 games do not run inside a pure PlayStation 2 environment. Memory access, system scheduling, disc I/O behavior, and video output are still mediated by PS3 system software. On full hardware systems this layer is thin. On hybrid systems, it becomes central.

Many PlayStation 2 titles were built around fixed timing assumptions that held on original hardware. Once CPU behavior is approximated in software, even small deviations surface. These failures are not random. Hybrid systems in particular show a documented set of incompatibilities numbering in the low hundreds when minor and major issues are combined, with only a smaller subset rendering games completely unplayable. Most problems cluster around FMV playback, streaming audio, and synchronization-heavy code paths.

Community testing points to a consistent pattern. Games such as Metal Gear Solid 3, Gran Turismo 4, Xenosaga Episode I and II, and Shadow of the Colossus illustrate where hybrid systems struggle: FMV desynchronization, audio timing drift, or streaming stalls rather than outright crashes. These are not obscure edge cases. They sit squarely in the mainstream of the PS2 catalog, which is why user reports often feel contradictory without model context.

These outcomes are structural. They reflect Sony’s decision to trade hardware cost for abstraction at a moment when the PS3 was already under thermal and financial pressure.

PS2 Graphics on PlayStation 3

PS2 graphics on the PlayStation 3 pass through the PS3’s digital output pipeline, which changes how games are presented compared to native PS2 hardware. Even when the PS2 Graphics Synthesizer is physically present, the final image is still processed for HDMI output, introducing scaling, filtering, and deinterlacing decisions the original PS2 never had to make.

The result is often a sharper but less forgiving image. Texture seams become more visible. Dithering and blending tricks designed for analog output can look harsher, exposing pixel structure that composite blur once concealed. Optional PS3 smoothing and upscaling features can improve perceived clarity in some titles, but they also reshape the image in ways preservation-focused players notice immediately.

These changes are not inherently wrong. They are simply different. PS2 games were authored for analog displays, and the move to a digital pipeline alters how many visual shortcuts behave once removed from their original context.

PS2 Audio and FMV Issues on PlayStation 3

Audio and full-motion video issues are the most common compatibility complaints on the PlayStation 3. FMV playback can stutter, audio can drift out of sync, and cutscenes can drop frames in games that stream data continuously or rely on precise timing.

On full hardware backward-compatible systems, these problems appear infrequently. On hybrid systems, they recur in predictable ways. Community testing has identified well over a hundred PS2 titles with known audio or FMV issues on hybrid models when minor and major problems are counted together, compared to a much smaller set on full hardware systems.

The difference comes down to timing. Disc access, buffering behavior, and CPU scheduling no longer line up the way they do on original PS2 hardware. When those relationships shift, audio and video are usually the first places the cracks show.

PS3 Models and Backward Compatibility Differences

The familiar fat versus slim distinction is misleading. On the PlayStation 3, backward compatibility is determined by internal architecture and model prefix, not by case design.

Full hardware backward compatibility exists only on launch-era North American and Japanese models labeled CECHAxx (60GB) and CECHBxx (20GB). These systems include both original PS2 chips and deliver the highest overall compatibility with PS2 discs.

Hybrid backward compatibility appears on European and Australian CECHCxx models and later North American CECHExx revisions. These retain the PS2 Graphics Synthesizer but replace the Emotion Engine with software emulation. Most games still run, but compatibility is measurably lower than on full hardware systems.

All later revisions, including CECHGxx and every Slim and Super Slim model, drop PS2 disc support entirely. These systems rely on digital PS2 re-releases where available. Across community testing, roughly 63 percent of tested titles run without issues, rising to about 76 percent when minor problems are accepted.

Region adds another layer. European backward-compatible PS3s were hybrid only and launched with explicitly limited compatibility. Disc region locks remain in place, and PAL titles can exhibit stutter or timing issues when played on NTSC hardware.

In practice, the fastest way to identify a backward-compatible PlayStation 3 is to check the rear label for the CECH model code. If the prefix does not match a known backward-compatible family, PS2 disc support is not present.

PS2 Memory Cards and Peripherals on PlayStation 3

PS2 games running on a backward-compatible PlayStation 3 use virtual memory cards stored on the system’s internal hard drive. To the game, these appear as standard PS2 memory cards and usually behave as expected.

Sony’s USB PS2 memory card adapter allows saves to be transferred from physical PS2 cards into these virtual cards. The process is reliable in most cases, but it is not identical to original hardware. A small number of titles that depend on direct memory card timing, multitap awareness, or mixed PS1 and PS2 save access can behave unpredictably.

Peripheral support is more limited. Lightgun games fail due to the absence of CRT timing and native lightgun handling. Multitap support is inconsistent and often restricted to the first controller port. Early DualShock 3 controllers also lack native rumble support in some PS2 titles.

These are not regressions. They reflect peripherals the PlayStation 3 was never designed to replicate at the hardware level.

PS2 Backward Compatibility Fixes on PlayStation 3 in 2026

Unlike the PlayStation 2, the PlayStation 3 does not allow PS2 backward compatibility to be meaningfully recovered once the underlying hardware is gone. There is no driver update or configuration tweak that can replace missing chips.

On non-backward-compatible PS3 models, custom firmware or HEN can enable PS2 game images to run through Sony’s software emulator using tools such as multiMAN or webMAN. This improves convenience, but it does not restore disc support and does not change the emulator’s limits.

On early backward-compatible systems, the most effective fixes are physical rather than software-based. Thermal maintenance, fresh compound, delidding, and in extreme cases RSX replacement are now the difference between a working system and a dead one. These interventions can extend lifespan, but they are invasive and costly.

In practice, PS2 backward compatibility on the PlayStation 3 in 2026 is not about tuning behavior. It is about choosing which compromises you are willing to accept.

Why PlayStation 2 on PS3 Backward Compatibility Has Limits

Sony’s backward compatibility strategy on the PlayStation 3 was constrained by cost, heat, and manufacturing yield. The PS3 was already a thermally stressed design, and adding extra chips increased complexity while amplifying long-term reliability problems.

Those tradeoffs became visible over time. Early full hardware backward-compatible systems rely on a 90nm RSX GPU closely associated with solder fatigue and heat-cycling failure. In today’s retro market, a large portion of surviving launch-era units have already failed, with real-world failure rates often exceeding half of remaining systems.

Hybrid backward-compatible revisions reduced that risk. Smaller fabrication nodes and lower heat output made later fat models more likely to survive into 2026, even as they sacrificed a small amount of compatibility accuracy. Once PS2 hardware was removed entirely, backward compatibility could not be brought back without redesigning the system.

Which PS3 Model Is Best for Playing PS2 Games? (Buyer’s Guide)

In practical terms, PS2-on-PS3 options form a clear hierarchy. Full hardware backward-compatible PS3 models offer the highest accuracy. Hybrid backward-compatible models trade a small amount of compatibility for far better survivability. Software-based options prioritize convenience. Original PS2 hardware and modern emulation remain the preservation benchmarks.

If PS2 discs are the priority and refurbishment can be verified, CECHAxx and CECHBxx systems remain the purist’s choice. They deliver behavior closest to native PlayStation 2 hardware, but ownership in 2026 is a gamble.

Hybrid models such as CECHCxx and CECHExx represent the most practical one-box solution for most libraries. They sacrifice a small percentage of compatibility in exchange for dramatically better odds of long-term survival.

Later PS3 revisions should be avoided for PS2 disc playback entirely. If disc accuracy matters, original PlayStation 2 hardware remains the most reliable and affordable option. Modern emulation now exceeds PS3 backward compatibility in flexibility, resolution, and consistency.

The PlayStation 3 did not solve backward compatibility. It exposed the cost of doing it properly, proved that hardware-based continuity could not scale, and moved on.