There was a time when Sony believed the future of gaming wasn’t just about games. It was about creating a place that belonged to everyone. In the late 2000s, as online play began reshaping how consoles connected people, Sony took a risk few understood at the time. They tried to build a world. And for a while, they did.

PlayStation Home wasn’t a service, Second Life, Facebook, or Xbox Live. It borrowed from all of them while reaching for something more. It was a living, breathing social environment made for a generation of players who were just beginning to understand that digital identity could be more than a gamertag.

And that idea didn’t come from a boardroom or a marketing team. It came from one game…

In the early 2000s, Sony’s London Studio was developing a sequel to The Getaway, one of the PlayStation 2’s most ambitious titles. As part of the concept for The Getaway: Black Monday, the team imagined a connected multiplayer space where players could gather before heading into the city. It was just a shared lobby, a simple pre-game room, but something about it stuck. They gave it a codename: The Hub.

The PlayStation 2 wasn’t built for that kind of vision. Its online functionality was clunky and fragmented, and most players never even connected the console to the internet. So the idea was shelved, but not forgotten. As work on PlayStation 3 began, the London team picked it back up and reimagined it. The Hub became something more. Not just a pre-game lobby, but a world of its own. And this time, it had a name. It was called Home.

The first prototypes began to take shape inside Sony Computer Entertainment Europe around 2005. By then, the PS3 was deep in development and was being positioned as more than a game console. It was a Blu-ray player, a media hub, a centerpiece for the connected living room. And it was expensive. The $499 base model and $599 version made the 2006 launch a rough introduction. Strong games were lacking, and Microsoft’s Xbox 360 had already been on the market for a year.

Sony needed something to justify the price, and that something appeared on March 7, 2007, when Phil Harrison took the stage at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco. At the time, he was President of Worldwide Studios at Sony Computer Entertainment. After being briefed on Home earlier that year, he immediately saw its potential. Standing before a crowd of skeptical developers and press, he didn’t just demo a feature. He presented a philosophy and called it Game 3.0.

Home would be a living 3D social network where players could create avatars, decorate apartments, meet in public plazas, play games, watch videos, and launch into multiplayer together. All of it would run in real time on the PlayStation 3.

The idea sounded futuristic, maybe even too ambitious. But it was free, and that mattered. PlayStation Home would be available to every PS3 owner at no cost, with optional purchases for virtual goods and branded content. At a time when Xbox Live was charging for basic access, Sony promised a full online world with no barrier to entry.

Internally, Sony poured resources into development. London Studio led the effort, with engineer James Levick and designer Oscar Clark helping shape the platform. Phil Harrison became Home’s highest-level supporter, and his involvement helped secure buy-in across Sony’s international divisions. That same structure, split between Japan, Europe, and America, would eventually create challenges. But for a time, the team had support, budget, and a clear vision.

Closed beta testing began quietly in 2007. Invitations were sent to select users, including those who had purchased specific items from the PlayStation Store, won online contests, or subscribed to Sony’s digital magazine Qore. What they found was a sparse but intriguing space. There was a central plaza, a bowling alley, an arcade with a few games, a movie theater, and customizable personal apartments. Players could meet up, chat, use emotes, dress up avatars, and invite friends into their spaces.

Development took longer than expected. Home missed its initial launch window and remained in closed beta throughout most of 2008. Sony continued refining it. They didn’t treat it as a traditional product with a launch date. It was meant to grow over time. And on December 11, 2008, PlayStation Home opened to the public.

Sony called it an open beta, still a work in progress, but it was finally available. You could download it from the PlayStation Store, load it up, and enter a world where your PS3 became something else. The reaction came quickly and was mixed.

Some players were captivated while others didn’t understand the point, and critics quickly pointed to the lack of content. The movie theater played little more than trailers, the bowling alley offered just a few lanes, and avatars moved with noticeable stiffness. Monetization was impossible to ignore as branded content appeared everywhere. Diesel ran a clothing store. Red Bull had its own island. Even the furniture for your apartment came with a price tag.

Still, people kept coming back.

By March 2009, Sony reported that over 4 million PS3 owners had entered Home. A few months later, that number reached 7 million. By the end of the year, it climbed to 10 million. Sony never revealed daily active user numbers, but downloads continued. In 2010, Sony celebrated the FIFA World Cup by launching a massive soccer-themed space inside Home. Players could watch live events, meet fans from around the world, and play football mini-games together. It marked one of the first times people from different regions shared the same digital space.

Home grew rapidly through 2010, fueled by weekly updates that added new clothes, areas, and games. Some of these were full experiences, like Sodium One, a 3D tank combat game developed by Outso and built entirely within Home. The virtual mall continued to expand, personal spaces became more elaborate, and events were regularly hosted to celebrate holidays, major game releases, and movie promotions. Players could attend parties, earn rewards, and show off their collections.

The platform itself also evolved. Sony reorganized Home’s layout, introduced new developer tools, and eventually added trophy support. In 2011, Home received its biggest update. The central plaza was replaced with themed districts. The interface became simpler, environments were updated, and load times improved.

Behind the scenes, Home was profitable. It didn’t make a ton of money, but microtransactions added up. Players paid for pets, premium spaces, exclusive furniture, and limited-edition outfits. In Japan, special events drew thousands of fans. In North America, Home hosted virtual E3 booths and live developer Q&A sessions. In Europe, players formed fashion clubs, organized game nights, and even built roleplaying communities.

At its peak, Home reportedly had more than 40 million registered users. Sony claimed tens of millions had logged in at some point. But by 2012, the momentum began to fade. The PlayStation 4 was in development, and Sony’s priorities shifted. Home was never ported to the new console or adapted for VR, and as updates slowed and events became rare, users gradually moved on.

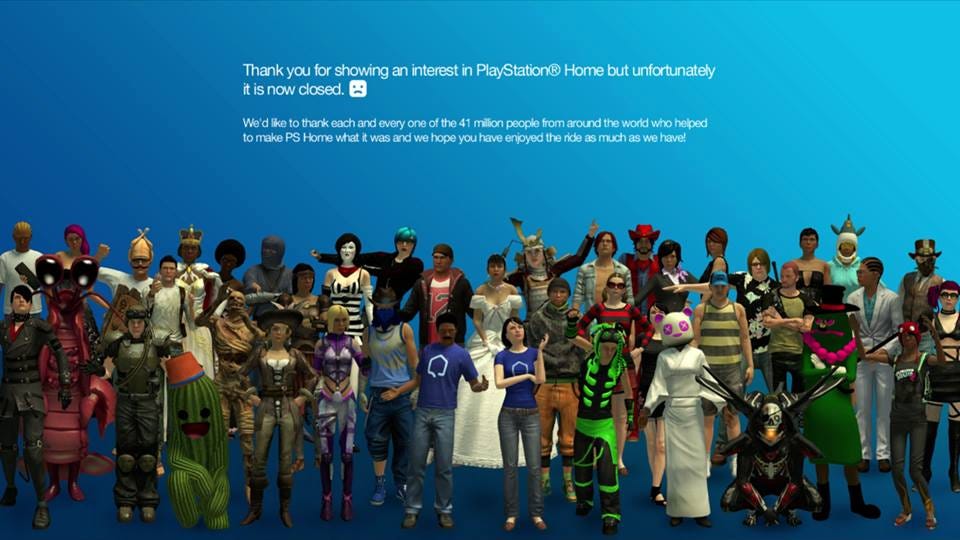

On August 22, 2014, Sony Japan quietly announced that Home would shut down in Asia. Content sales would end in September, and the service would close in March 2015. A few weeks later, Sony Europe and America made similar announcements. On March 31, 2015, PlayStation Home closed worldwide.

There was no ceremony and no last-minute revival. Just a message of thanks, a final login, and then silence.

But the story didn’t end there.

In the years that followed, Home became something larger in memory than it ever was in practice, with fans viewing it less as a failure and more as a missed opportunity. It was seen as a platform ahead of its time, a metaverse before the word went mainstream. Preservation communities took on the long task of saving what they could, reconstructing server code, launching reverse engineering efforts, and eventually piecing together a playable version that ran on modified PS3 hardware and preserved a small piece of what once existed.

Retrospectives came later. Journalists and players began to reevaluate what Home had tried to be. It wasn’t perfect, and it certainly wasn’t finished, but it felt alive. While it never became a commercial success, it still meant something to the people who spent time in it. The ideas it explored, from avatar identity to live events and digital economies, became the foundation for what came next. Fortnite, Roblox, and even VRChat owe a small part of their DNA to Home.

Sony never tried again. Home never returned.

But for millions of players, it never really left. It was a moment when the PlayStation 3 became a portal. Not to a battlefield or a mission, but to a space where you could simply exist. And for many, that was enough.

I really liked Home, and I enjoyed my time there. My hope was that it would eventually morph into a Sony-based metaverse, and maybe it would have someday. An idea ahead of its time I think.

I miss PlayStation Home so damn much. I have so many fond memories of that place doing stuff like survival Bomber in the Bomberman space and dancing in the Ratchet & Clank space. One of the cool things I bought was a Ratchet & Clank apartment where you'd occasionally see Aphelion fly by outside the windows.