Blu-ray Explained: How It Works, Why It Beat HD DVD, and Why It Was the Last Physical Media Standard

How the PlayStation 3 turned Blu-ray into the last physical media format to succeed at scale

In simple terms, Blu-ray is a high-capacity optical disc format created to replace DVD for high-definition video. By using a blue-violet laser with a shorter wavelength than DVD’s red laser, it could store far more data on the same-sized disc, making full high-definition video, lossless audio, and advanced interactive menus practical on physical media.

Blu-ray is often remembered as the winner of the format war between Blu-ray and HD DVD. That framing tells you the outcome, but it obscures the mechanism that decided it.

The real answer sits somewhere else, less about specifications and more about how the format was positioned, distributed, and made unavoidable before consumers ever had to choose.

Blu-ray did not win on technical specifications alone. Its success came from Sony treating it as infrastructure rather than a product, and being willing to carry the cost of that decision longer than anyone else.

Blu-ray was not built by Sony alone. It emerged from the Blu-ray Disc Association, a coalition that included Panasonic, Philips, Pioneer, and other major electronics and media companies. Philips contributed foundational optical disc research and physical disc structure, while Panasonic played a critical role in professional authoring tools and studio workflows. What Sony uniquely controlled was scale. Through consumer hardware, content relationships, and eventually the PlayStation 3, Sony solved the distribution problem that no standards body could address on its own.

For Sony, Blu-ray was about regaining control over a standard, something the company had lost with DVD. Control in this context did not imply consensus or goodwill, but leverage built through scale, timing, and financial pressure applied across the ecosystem.

Sony placed the project under the leadership of Masanobu Yamamoto, a veteran engineer who had previously worked on the original Compact Disc in the late 1970s. His role reflected Sony’s intent to avoid a repeat of past format battles by balancing engineering ambition with industry alignment.

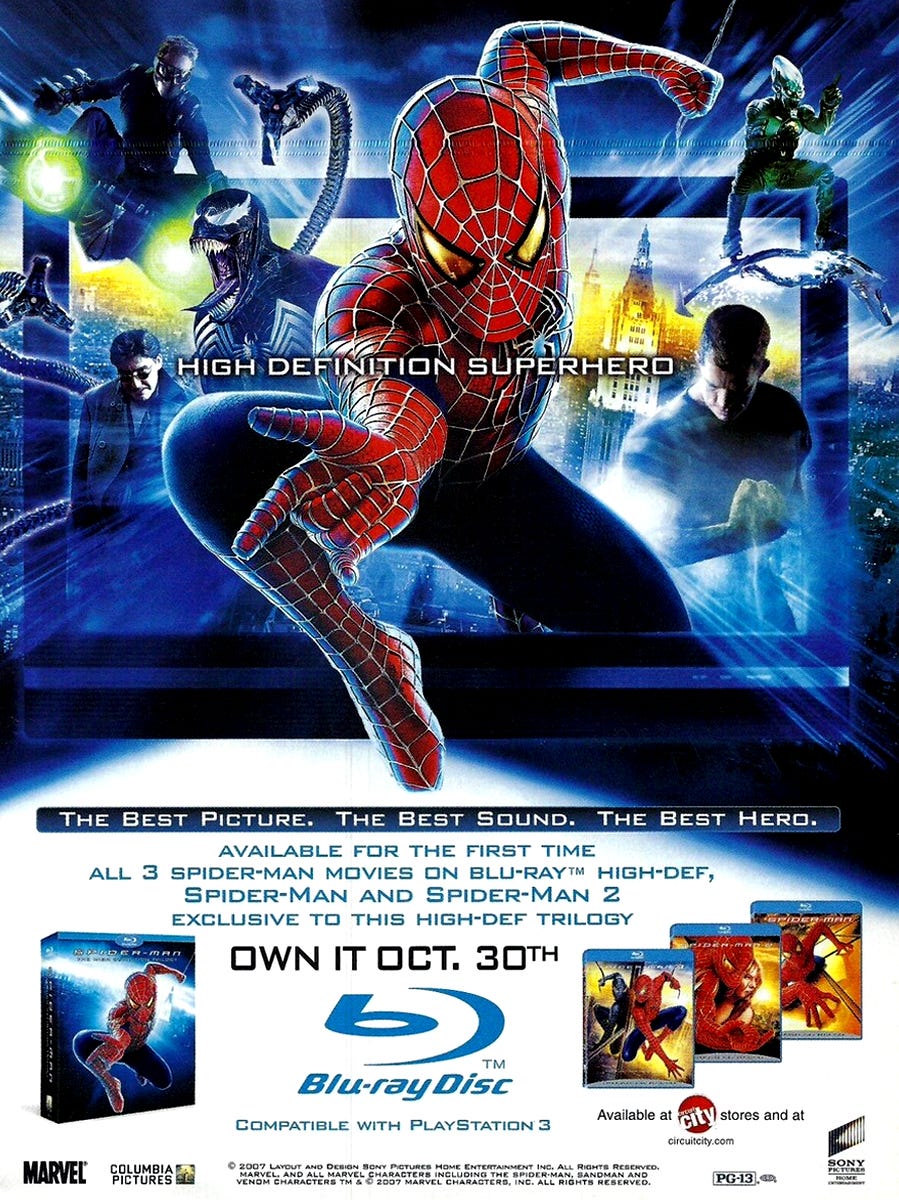

The turning point was the PlayStation 3. By shipping a Blu-ray drive inside every console, Sony placed millions of Blu-ray players into homes that never intended to buy one. What looked like a risky console launch doubled as the largest physical media rollout in history.

This article explains how Blu-ray works, why it was built the way it was, how the PlayStation 3 reshaped the format war, and why Blu-ray became the last physical media standard to succeed at scale, even as the industry drifted toward streaming.

Why DVD Could Not Support High-Definition Video

By the early 2000s, DVD had reached a hard technical limit. High-definition video was moving toward 1080p, higher bitrates, and lossless audio, but DVD’s storage capacity and data throughput could not keep up.

The limitation was physical. DVD relied on a red laser with a longer wavelength, which restricted how tightly data could be written to the disc surface. Even dual-layer DVDs topped out at 8.5GB, forcing studios to rely on heavy compression, reduced audio quality, or simplified menus to make high-definition content fit.

Research into shorter-wavelength blue-violet lasers had been underway since the 1990s. Smaller pits and tighter track spacing allowed far higher data density without increasing disc size. A disc using that laser could store 25GB per layer, making true high-definition video practical on physical media.

Blu-ray emerged because DVD could not scale to the next generation of video at meaningful quality, bitrate, and duration. This limitation led many consumers and studios to ask why DVD could not simply be upgraded to handle high-definition video, rather than replaced entirely.

How Blu-ray Works: Blue Laser, Disc Capacity, and Data Rates

Blu-ray keeps the same basic idea as DVD. A plastic disc spins under a laser, and data is read as microscopic pits arranged along a spiral track. The difference is scale.

DVD’s red laser limits how tightly data can be packed. Blu-ray’s blue-violet laser has a shorter wavelength, allowing much smaller pits to be placed closer together. The disc does not get bigger. The data density increases dramatically.

Unlike earlier optical formats, Blu-ray was designed around high-definition video as a baseline rather than an upgrade. DVD adapted to HD through compression and compromise. Blu-ray assumed higher bitrates, larger files, and advanced audio from the start. That assumption shaped disc capacity, interactive systems, and the professional authoring tools built around the format.

A single-layer Blu-ray disc holds 25GB of data, with dual-layer discs reaching 50GB. This made it possible to ship high-bitrate 1080p video, lossless audio formats, and full-featured menus without compromise. Higher sustained data rates reduced the need for aggressive compression and allowed films to be delivered closer to their theatrical masters.

Blu-ray places its data layer closer to the disc surface to improve precision. Early concerns about durability were addressed through hard-coating technologies that protected the disc without affecting readability. Like all optical media, Blu-ray discs remain subject to manufacturing defects and long-term degradation. In recent years, collectors have documented a growing number of Blu-ray playback failures across a wide range of studios and release dates. These failures, commonly grouped under the term disc rot, are increasingly understood as an ongoing manufacturing and sealing risk rather than a closed historical issue. Multi-layer discs appear especially vulnerable, and failures have been reported even in sealed copies, complicating assumptions about long-term reliability. In practice, Blu-ray proved no more fragile than DVD.

Blu-ray vs HD DVD: Why Blu-ray Won the Format War

From Toshiba’s perspective, HD DVD was not a weaker format but a more conservative one, optimized for lower manufacturing costs, faster authoring, and immediate reliability rather than long-term capacity.

Blu-ray did not enter the market alone. Toshiba’s HD DVD targeted the same future but approached it differently.

HD DVD stayed close to DVD’s physical structure, making discs cheaper to manufacture and easier for studios to author. Capacity was lower, but often sufficient. Menus were fast, tools were mature, and early releases were consistent. Backed by Microsoft, Intel, and Universal, HD DVD positioned itself as the practical transition.

HD DVD also benefited from a simpler interactive layer. Its iHD system, built on XML, delivered fast, responsive menus at launch. Blu-ray relied on Java-based BD-J, which proved slow, inconsistent, and highly dependent on player firmware. Early Blu-ray discs often felt unfinished not because of hardware limits, but because the software layer lagged behind the format’s ambitions.

Licensing was also important. HD DVD emerged in part because the DVD Forum resisted the higher licensing costs associated with Blu-ray, making HD DVD attractive to manufacturers wary of another tightly controlled standard.

Blu-ray stumbled early. Many first-generation releases used MPEG-2 encoding and single-layer discs, leading to uneven image quality. In early releases, HD DVD often appeared more polished, with consistent encoding and faster menus, while Blu-ray’s ambitions outpaced its software maturity. Dual-layer discs arrived slowly. Hardware was expensive and firmware updates were frequent. To outsiders, Blu-ray looked overengineered and unfinished.

Sony avoided a purely technical fight. Instead, it built alliances. Studios, hardware manufacturers, and distributors were organized under a shared standard to create momentum rather than perfection. Both camps engaged in aggressive studio courtship, combining co-marketing, financial incentives, and strategic commitments. These efforts were opaque by design, making it difficult to separate economics from allegiance in the public record. Blu-ray did not need to be flawless. It needed to be established before the market settled.

For a time, HD DVD looked like the safer choice. In its first year, HD DVD briefly outsold Blu-ray hardware in several markets due to lower prices and more consistent early releases. At the height of the disc format war, consumers were asking which format was better, Blu-ray or HD DVD, and whether either would last long enough to justify buying into it. Then the equation changed.

How the PlayStation 3 Made Blu-ray the Default Standard

The format war did not turn on a press release. It turned when the PlayStation 3 entered living rooms.

By bundling a Blu-ray drive into every PS3, Sony collapsed the distinction between console and media player. Millions of households acquired a Blu-ray player without comparing formats or committing to a new disc standard. They bought a console. Blu-ray arrived with it.

That distinction was important because early standalone Blu-ray players were slow, expensive, and inconsistent. The PS3 was overbuilt by comparison, with processing headroom, a fast optical drive, and a network connection designed for firmware updates. When authoring practices changed or new features appeared, the PS3 adapted in software rather than hardware.

Scale followed naturally. As PS3 production ramped up, Sony was seeding the market with millions of Blu-ray drives each year. HD DVD relied on optional players and accessories. Blu-ray rode inside a product people already wanted.

Blu-ray did not win because it was cheaper or simpler. Many later explanations reduce its success to a console bundle, but the real question is how the PlayStation 3 changed the economics of the entire format war. It won because Sony solved the distribution problem. By embedding Blu-ray into the PlayStation 3, Sony made the format unavoidable before the market had time to reject it.

Once Blu-ray stopped being a choice and became an assumption, the outcome was no longer in doubt. Blu-ray won because Sony solved distribution before the market had time to decide whether it wanted physical media at all.

How the HD DVD Format War Collapsed

By late 2007, the war stopped being about specifications and became about risk. Supporting two formats made sense only while the installed base remained uncertain.

As PS3 adoption grew, that balance broke. Retailers shifted shelf space. Studios followed. When Warner Bros. announced it would release exclusively on Blu-ray in January 2008, ambiguity disappeared. That decision was the visible breaking point, following months of shifting economics driven by the PlayStation 3’s growing installed base. The market aligned almost immediately.

HD DVD did not fail because it was unusable. It failed because its ecosystem evaporated. Fewer releases led to fewer players. Fewer players made continued support irrational. Toshiba’s withdrawal in early 2008 confirmed what the market had already decided.

Blu-ray won by making the alternative untenable.

Why Blu-ray Peaked as Streaming Took Over

Blu-ray reached maturity at the worst possible moment.

As the format stabilized and delivered consistent quality, consumption habits were already shifting. Streaming normalized instant playback, and improving broadband made convenience more valuable than fidelity for most viewers.

Blu-ray demanded commitment. Buying discs. Managing firmware updates. Living with region locks and load times. Blu-ray simplified regional controls compared to DVD but did not remove them, preserving studio control at a moment when consumers were becoming accustomed to borderless digital access.

Technically, Blu-ray succeeded. Picture quality surpassed DVD. Lossless audio entered the living room. Studio masters could be delivered without compromise. Streaming did not need to be better. It only needed to be easier. Aggressive DRM, region locking, and frequent firmware updates added friction that made Blu-ray feel demanding at a moment when streaming offered instant access.

Blu-ray split into two markets. A shrinking retail footprint alongside a boutique collector ecosystem where quality, packaging, and permanence still mattered. As retail support collapsed and major chains exited disc sales, Blu-ray’s presence narrowed further, reinforcing its shift from mass format to collector medium. Streaming absorbed the mainstream audience. Blu-ray became the premium option by default.

How Blu-ray Scaled to 4K Without Becoming a New Format

The move to 4K extended Blu-ray rather than replacing it.

Ultra HD Blu-ray kept the same disc size and optical principles, but pushed the system further. Resolution increased, but the real changes were compression, capacity, and data rate. HEVC encoding made high-quality 4K practical on disc. Triple-layer and quad-layer discs expanded capacity to 66GB and 100GB. HDR support widened color and contrast beyond what streaming could reliably deliver.

This transition did not trigger another format war. Streaming had already claimed the mass market. Ultra HD Blu-ray launched as a premium format by design, supported by dedicated players rather than consoles. Compared to streaming 4K, Ultra HD Blu-ray offers higher and more consistent bitrates, full-resolution audio, and physical ownership rather than access tied to a service.

Blu-ray as an Endpoint

Blu-ray was built to solve a specific transition, delivering high-definition video into homes before digital infrastructure could carry that load reliably.

In that role, it succeeded completely. It standardized HD delivery, reshaped authoring pipelines, and turned the PlayStation 3 into a media device as much as a console. What followed was not decline, but displacement. Streaming changed the goal from ownership to access.

In 2026, Blu-ray turns twenty years old. This is notable not because the format is aging, but because nothing has replaced it. No physical media standard since has crossed into the mainstream at that scale, and none is likely to again.

Blu-ray closed a chapter.

As an endpoint, Blu-ray is less a victory monument than a boundary marker. It defines the last moment when physical media could still align with mainstream distribution, before economics and convenience diverged permanently.