By the end of the 1980s, Sony had been in the computer game for nearly a decade. It introduced the 3.5-inch floppy disk with the Series 35 word processor, launched the SMC-70 for business, joined the MSX movement, built UNIX workstations, and experimented with hobbyist machines under the Hit Bit name. But for all the innovation, there was still no clear breakthrough. Sony had tried almost every angle, but nothing had positioned the company as a serious force in personal computing.

And then Japan hit a new wall. Western PCs couldn’t handle Japanese. They couldn’t display kanji properly, couldn’t format vertical text, couldn’t meet the basic needs of Japanese businesses. The industry needed a new direction.

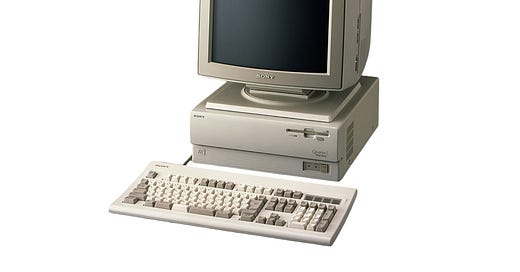

The solution became AX, a standardized platform designed to make IBM-compatible PCs fully functional in Japanese. The idea was first conceived by Kazuhiko Nishi before stepping down as vice president of Microsoft. After his departure, Microsoft Japan took over the project and teamed up…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Obsolete Sony’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.